The literature I reviewed provided me with a foundation for the exploratory and generative phases. While I focused on intimate relationships and conversation, I made a deliberate decision to look for literature not directly related to my core topic, but still focused on concepts and ideas I believed would benefit my thesis, such as Bernice McCarthy's 4MAT system and Elizabeth Shove's Three Elements. The literature I reviewed ranges from texts focused on conversation, intimate relationships, and interfaces, to learning theories and theoretical frameworks. Below is a description of my literature reviews, organized as a set of guiding questions that I investigated.

Kinda Human / Literature Review

What is conversation?

I began my review by establishing an understanding of conversation. While this section of the review was derived mainly from my earlier paper, "A Consideration of Today's Conversational Interfaces Courtesy of Cybernetics and Yesterday's Conversational Interfaces," I also put a considerable amount of effort into deepening that study of literature with a specific focus on the work of Hugh Dubberly and Paul Pangaro.

I was particularly interested in Dubberly and Pangaro's description of the "models of interaction"; "at one extreme ... simply reactive systems, such as a door that opens when you step on a mat or a search engine that returns results when you submit a query. At the other extreme is conversation. Conversation is a progression of exchanges among participants" (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2009). Today, we see such "progression" (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2009) or "continuous action conceived or presented as onward movement through time" (Progression, 2019), being achieved very rarely when an artificial agent is involved. This lack of "progression" (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2009) can thus be attributed to conversation being a "highly complex type of interaction ..., for conversation is the means by which existing knowledge is conveyed and new knowledge is created" (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2009). Such complexity sheds light on why the artificial agents we commonly interact with are unable to augment conversation today (i.e., assist an individual in improving their communication of information).

How can one navigate the complexity the complexity of conversation?

To overcome this complexity, Dubberly, Pangaro, Pask, and others have developed models that serve as a "way of thinking... [that] involves concepts" (von Glasersfeld, 1995, p. 146) and their formation and the creation of relationships between them.

One particular framework, Gordon Pask's (1976) Conversation Theory, presents a "formalism for describing the architecture of interactions or conversations, no matter where they may arise or among what types of entities" (Pangaro, 2002). Dubberly and Pangaro (2009) have also worked to simplify Pask's (1976) theory into six main tasks that comprise the "Process of Conversation" (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2009): the opening of a channel, a commitment to engagement, the construction of meaning, evolution, a convergence on agreement, and an action or transaction. They have also worked to clarify these steps into five main "requirements for conversation," which include "[the] establish[ment] of [an] environment and mindset", "[the] use of shared language", "[an] engagement in mutually beneficial, peer-to-peer exchange", "[a] confirmation in shared mental models", and "[an] engagement in a transaction - [the] execution of cooperative actions" (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2009). Conversation Theory, Dubberly and Pangaro's "Process of Conversation" (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2009) and "requirements for conversation" (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2009) bring attention to aspects and considerations designers should consider and employ when working with artificial agents. While some of the artificial agents we see today do address a number of these requirements, one would be extremely hard pressed to present an artificial agent that addresses all of them.

Dubberly and Pangaro, "Process of Conversation"

Others researchers including Erika Hall, Paul Grice, and W. Ross Ashby have also created related models. Hall has looked at the ways interaction can be "truly conversational" (Hall, 2019, Error Tolerant, para. 3) and described the "elements of a conversation" as being the system or "a set of interconnected elements that influence one another", the interface or "a boundary across which two systems exchange information", and an interaction or "the means by which the systems influence each other" (Hall, 2019, Interactions Require Interfaces, para. 1). Grice has taken a slightly different approach and developed the Gricean Maxims which describe the characteristics of productive communication (e.g., quantity, quality, relation, manner; Grice, 1975). At the same time, Ashby has created a visual model differentiating between the "immaterial aspects" and the "physical world" to show that "actions take place in the physical world, while goals do not. Goals, the province of cybernetics, are the 'immaterial aspects' of interaction" (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2011).

Grice, "Gricean Maxims"

Together, these models have provided me with a "way of thinking" (von Glasersfeld, 1995, p. 146) about the conversations I motivate between intimate partners. This led me to ask, how could these models inform the design of artificial agents so they could negotiate the complexity of conversation?

How could models of conversation inform the design of artificial agents?

In order to answer this question, I studied the evolving landscape of artificial agents and artificial intelligence by looking into early conversational interfaces (i.e., Musicolour and The Coordinator) and how each represents "an intelligent interface" (Kaplan, 2013).

Musicolour was "a sound-actuated interactive light show" (Bird & Di Paolo, 2008) designed by Gordon Pask. Pask created a machine in which "the performer ‘trained the machine and it played a game with him. In this sense, the system acted as an extension of the world with which he could cooperate to achieve effects... [he] could not achieve on his own.'" (Bird & Di Paolo, 2008) Musicolour reveals that addressing the "requirements for conversation" (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2009) enables a conversation between a human and artificial agent.

Pask, Musicolour: Stage and Projection Screen, Playbill

The Coordinator is also an example of an experience that enables a conversation between humans and artificial agents. The system was designed by Terry Winograd to "provide facilities for generating, transmitting, storing, retrieving, and displaying messages that are records of moves in conversations" (Winograd, 1987). Unlike Musicolour, which interpreted the actions of a human, The Coordinator enabled humans to interpret the actions of another while providing the structure for those actions by fulfilling the different "requirements for conversation" (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2009). For instance, The Coordinator would provide "different implicit structures of action" (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2009) to both develop a collective mindset and shared language. It ultimately serves as an example of how a concern for the dynamics of conversation can inform the design of an artificial agent capable of negotiating the complexity of conversation.

Winograd, The Coordinator: Converse Menu

Throughout my literature review, I began to realize that I had been focusing on historical artificial agents that were successful in achieving some degree of man-computer symbiosis. In order for me to design the artificial agents I aspired to create, I would need a better understanding of symbiosis.

What is symbiosis?

J.C.R. Licklider's paper "Man-Computer Symbiosis" describes it as a "close coupling between the human and the electronic members of the partnership" (Licklider, 1960, p. 4), which is a concept that could serve as a framework for potential relationships between humans and artificial agents. I recognized that Licklider's focus on partnerships where humans "set the goals, formulate the hypotheses, determine the criteria, and perform the evaluations" (Licklider, 1960, p. 4) while "computing machines... do the routinizable work that must be done to prepare the way for insights and decisions" (Licklider, 1960, p. 4) could serve as the standard for artificial agents in conversation with humans.

I also looked into others who had similar ideas. This includes Warren Brodey and Nilo Lindgren who wrote about technology "deftly pushing, rhythmizing his interventions to our 'natural' time scale so as not to push us over to radical instability" (Brodey & Lindgren, 1967, p. 94). These different interpretations of symbiosis that involve technology led me to my understanding and realization that if I am operating withinthe context of intimate relationships, where there is an increased possibility for emotion to supersede logic, then it is essential that I create an experience capable of achieving some degree of symbiosis.

With this understanding of symbiosis, I began a study of literature focused on intimate relationships and the different aspects of those relationships I would need to consider to design an artificial agent capable of enhancing an intimate partners' capacity for expression and understanding.

What are intimate relationships?

I learned that intimate relationships are comprised of "knowledge, caring, interdependence, mutuality, trust, and commitment" (Miller, 2012, p. 2), and while the same components comprise casual relationships, they often do not include the vast amounts of social dimensions that partners experience with each other when involved in an intimate relationship.

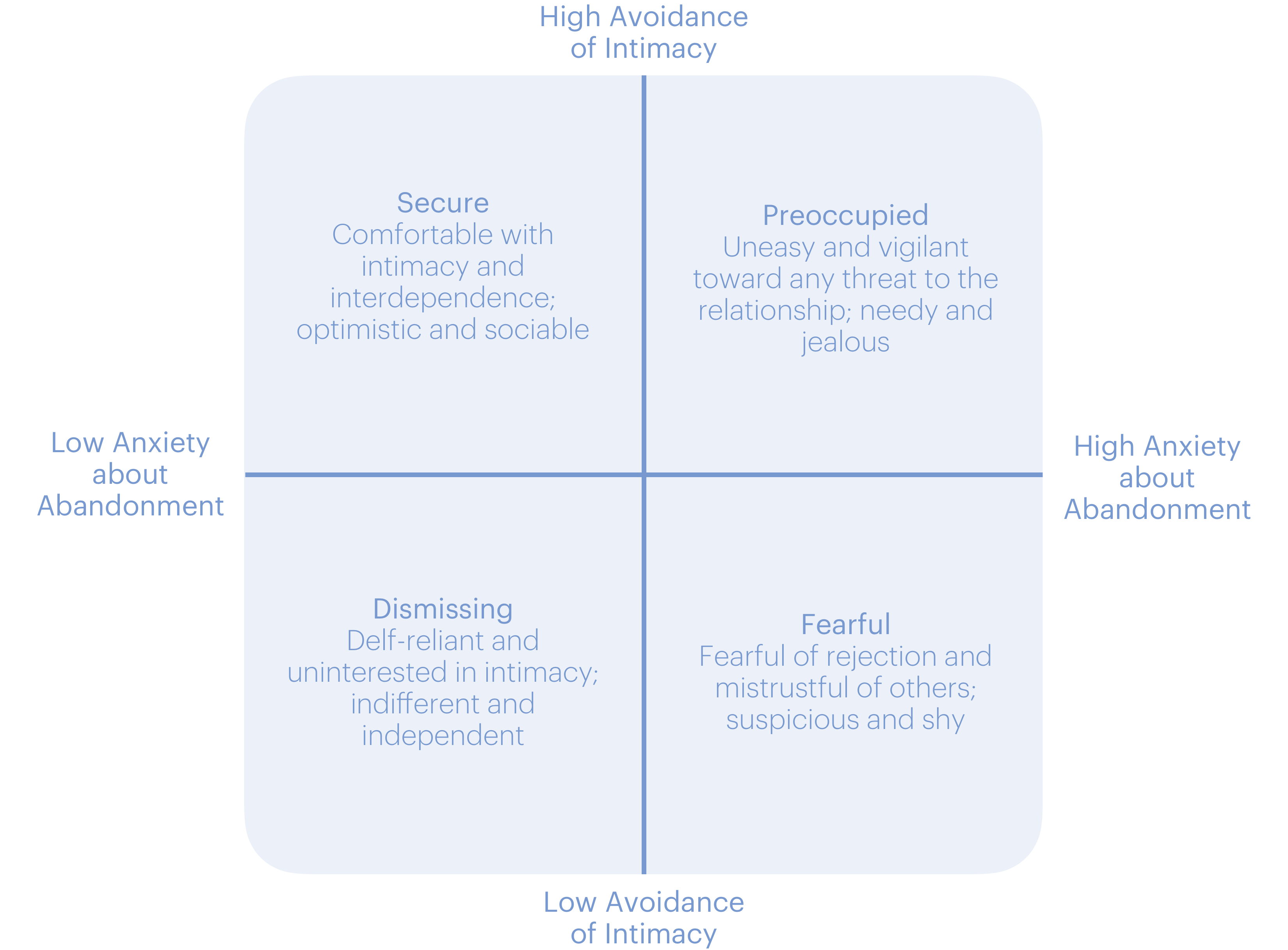

My reading of Miller and others in this area, introduced concepts including XYZ statements (i.e., when you do X in situation Y, I feel Z; Miller, 2012, p. 169) and negative affect reciprocity (i.e., when partners reciprocate negative affect; Miller, 2012, p. 348), that I embedded into interfaces. Frameworks like the four styles of attachment (i.e.,secure - autonomous, avoidant - dismissing, anxious - preoccupied, and disorganized - unresolved; Miller, 2012, p. 17), the four types of relationships (i.e., happy and stable, happy and unstable, unhappy and stable, and unhappy and unstable; Miller, 2012, p. 179), and John Gottman's four fighting styles (i.e., validating, volatile, conflict-avoiding, and hostile; Miller, 2012, p. 353) were also uncovered and all informed the interactions I would eventually design.

Four Styles of Attachment

I was also able to expand my search and talk to therapists and interpersonal relations researchers where I learned that the power of therapy (e.g., marital therapy and other forms) primarily lies in the unique space it provides, which at times can seem sacred. With this information, I was able to recognize the care and time that I would need to put into the environments the interfaces and artificial agents I design. This ultimately led me to my next question and to a review of literature focused on interfaces.

How do you create an environment capable of integrating an artificial agent into the everyday life of intimate partners?

The contextual environment plays a crucial role in an artificial agent effectively integrating itself into an intimate relationship. To better understand the theory behind such an environment, I looked into the concept of an interface.

In his research on fluid dynamics James Thompson first defined interfaces as "a dynamic boundary condition describing fluidity according to its separation of one distinct fluid body from another" (Hookway, 2014, p. 59). It is interesting to note Thomson's use of the word "fluidity" (Hookway, 2014, p. 5) or "the quality of flowing easily and clearly" (Fluidity, 2019). For an artificial agent to successfully integrate itself into the conversations of intimate partners, it would need to "easily and clearly" (Fluidity, 2019) interact with the other "distinct" (Hookway, 2014, p. 4) system.

Hookway also argues that an interface "might seem to be a form of technology, it is more properly a form of relating to technology, and so constitutes a relation that is already given, to be composed of the combined activities of human and machine" (Hookway, 2014, p. 1). This distinction is crucial because it focuses on the relations the interface prescribes on itself and those interacting with it (i.e., a person, another interface). It also emphasizes the need to carefully consider the interfaces and artificial agents designers create. This will ensure such designs are prescribing qualities that allow for human-machine symbiosis and for intimate partners to enhance their capacity for expression and understanding.

With this in mind, I concluded my review of the literature with three areas in mind (learning theories, ethics, and theoretical frameworks); fields that will help me prescribe the qualities capable of enabling a beneficial conversation between intimate partners.

What learning theories might my project benefit from?

A number of learning theories that I found in my review of literature served as frameworks to help users effectively grasp the concepts I present to them via an artificial agent. This includes McCarthy's 4MAT system—a simple and effective way of moving through learning (McCarthy, 1980) and Julie Dirksen's Learning Incline—a model that depicts the need for supports when an individual is confronted by a steep learning curve (Dirksen, 2012). Both concepts illustrate the need to teach complex content through a set of activities that build on top of each other.

McCarthy, 4MAT System

Dirksen, Learning Incline

What ethical considerations should I make?

While it is crucial to design an artificial agent capable of enhancing an intimate partners' capacity for expression and understanding, it is also important to consider the ethics of these agents. In studying literature around this, I found a particular interest in ELIZA, a system designed by Joseph Weizenbaum that enables humans (Weizenbaum, 1966) to communicate through a typewriter to a simulated psychologist. ELIZA imitated "the categorized dyadic natural language" of a psychiatric interview, which enabled a "speaker to maintain his sense of being heard and understood" (Weizenbaum, 1966). ELIZA ultimately led its creator, Joseph Weizenbaum, to be "revolt[ed] that the doctor's patients actually believed the robot really understood their problems...[and that] the robot therapist could help them in a constructive way" (Wallace, n.d.).

It also illustrated the care a designer needs to possess to ensure that the interfaces they design include responsible representations of artificial agents. Such artificial agents would not lead a speaker to believe they are speaking to a human when they are speaking to an agent and acknowledges what make us different from an agent.

What theoretical frameworks might my project benefit from?

Lastly, I considered and employed several theoretical frameworks from which my project could benefit. For instance, I used Don Ihde's human-machine relations as a tool to aid the framing of an experience. Ihde describes the differences between embodiment (i.e., use is not transparent, individual embodies the artifact; Angus, 1980, p. 321), hermeneutic (i.e., involves interpretation of the world mediated by an artifact), alterity (i.e., when an artifact is experienced as a "quasi-other" (Angus, 1980, p. 321)), and background relations (i.e., when an artifact is located at the periphery of human attention).

I found these relations to be helpful when thinking of potential concepts, and the benefit of having an artificial agent relate to a user in very different ways. Elizabeth Shove's "bundle of three elements: 'material artifacts, conventions and competences'" (Shove et al., 2008: 9) also provided me with a framework to consider when designing an experience. With the majority of aspects that comprise an intimate relationship deeply integrated into different practices (i.e., within the practice of marriage, there are numerous social meanings, personal meanings, procedures, structures, and artifacts), Shove's framework illustrates the need to understand the different practices that are "inextricably linked" to marriage and dating. This information helped me design artificial agents that can integrate successfully into partnering practices.